Working at sea is something which Mourne men are renowned for, but in the 1800s some men chose to work away from the locality of Kilkeel. Working on large ships was a dangerous employ but it was a job which provided a steady income along with guaranteed meals and the promise of seeing the world. Two Kilkeel men who left their homes to venture across the oceans on large ships were John Boyd and James Alexander Beck.

Letters from John Boyd to his father David Boyd in Kilkeel.

John Boyd was working onboard The Venus.

- He wrote this letter from Belfast, 3 March 1816

‘I did not join the Venus to the Tuesday following [Sunday]. I do not think we will sail before this day eight days on.’

‘I was much surprised to see two boys from Derryogue on my going into the office…wanting to get bound to the sea which it was impossible for them to get done on account of so many boys being in the trade.’

John however put in a good word for them and they were put under his care on the Venus. The two boys from Derryogue were called Jack McConnell and Tom Burns. John wanted his father to write him before he left Belfast. He gives his best to his mother, family and the Green family, finishing the letter, ‘Your loving son, John Boyd.’

- From Belfast, 8 September 1816

John writes that he wished to see his father but will just have to wait until it ‘please God I come back again.’

He received some shirts from his father and is under ‘great many obligations for your kindness’ and hopes in time he will be able to repay him. He wishes his father to say no more about him not having to pay him back as he ‘would be but a very ungrateful son if [he] could not give more than that to [his] father.

He goes on to talk about an ‘awful scene’ on Friday last. It was in reference to ‘the execution of the two unfortunate men opposite the Castle wall in High Street.’ He said it was a wet day but you still could not move in High Street or Donegal Place with the military and crowds of onlookers. He observed that it seemed ‘the poor fellows [were] reconciled to meet their fate.’ They were buried at Knockbracken in one grave and he was told that it was the largest funeral ever seen in Belfast. The two men were reportedly executed for burglary and this was the last public execution to take place in Belfast.

John mentions meeting a Bob McKee and closes the letter with ‘and I remain your loving son John Boyd.’

- From Belfast, 1 January 1817

John tells his father that he has arrived safely back in Belfast Monday last after a short but very severe passage. He couldn’t write him from London because there was too much going on after the loss of two ships. He was also sorry about informing his father about the loss of the Kelly. All hands and 17 passengers were lost on Sunday past on the banks of Liverpool.

John tells his father that his friend from Derryogue, Tom Burns has left the ship to go home despite him trying to persuade him otherwise; ‘I suppose he got frightened of the sea this last passage home. He can let you know all about me.’ He finishes this letter with the remark, ‘remaining your ever loving son to death, John Boyd.’

In all the letters John always asks about his family, Mrs Hallyday, Miss Vance and the Green family.

During his time at sea between May 1814 and February 1815 John visited London, Gosport, Gibraltar, Lisbon and Milford. His pay on board the ship was £3 per month.

The Diary of James Alexander Beck to Mary Ann McBurney of Derryogue during the voyage of the RMS Oroya which left London 23 November 1888.

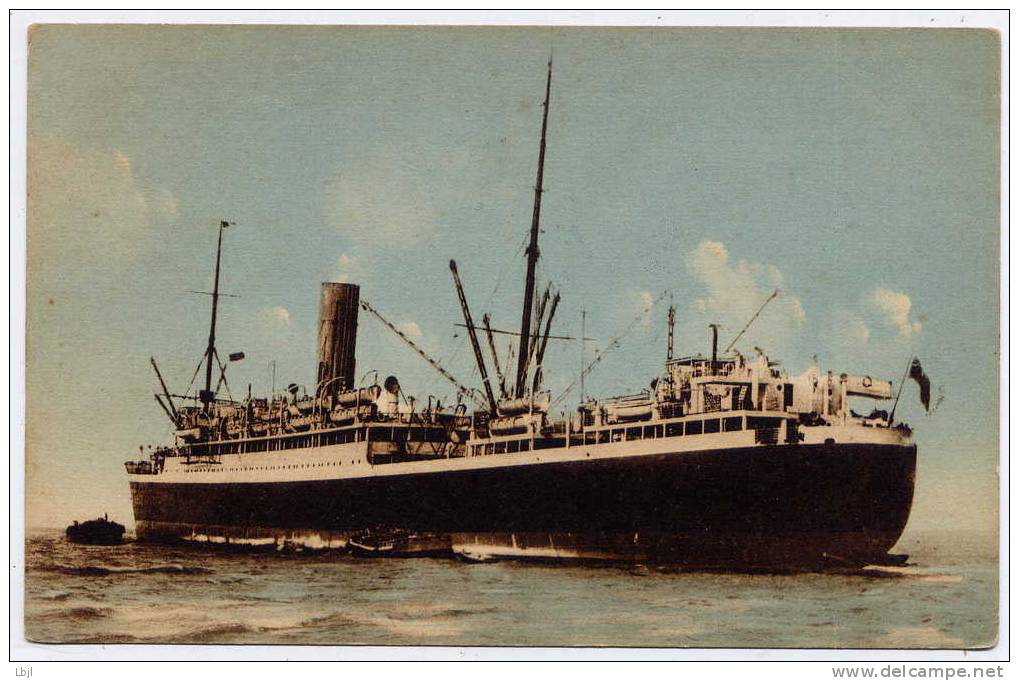

The Pacific Steam Navigation Co’s RMS Oroya was built by Barrow Ship Building Co. and was designed for a sailing service to Australia. She was launched 31 August 1886 and later sold to the Royal Mail Line in 1906. She was renamed Oro for her final voyage and was broken up in Italy in 1909.

One man who was working on board this ship during one of its trips to Australia was Kilkeel man James Alexander Beck. He kept a daily journal of the day to day goings on aboard the ship for his wife Mary Ann McBurney from Derryogue. His voyage lasted from November 1888 to 4 January 1889. His writings can give us a sneak peek into what life aboard a large steam ship would have been like.

The first few entries tell us of the ship encountering many bad storms and he writes that most people were suffering from extreme sea sickness. He was very glad when they passed the Bay of Biscay as the worst part of their journey was now over. They were on their way to Gibraltar.

James spent Christmas Day at sea and joined in with the rest of the ship hands wishing one another a Merry Christmas. They wanted to make the day as pleasant as possible and some started to sing Christmas carols. They had a dinner of soup and potatoes with fresh pork and plum for their main, followed by a small pie. For dessert they had tea and bread with jam and then finished it all with a small bun.

His Christmas Day entry is very poignant and it is clear he was missing home; ‘I often think of home today and when I think of the past Xmas I spent with you… I can surely say that this one is the worst I have spent for years… We have gained nearly seven hours since we left so that one can almost tell on a day like this what you are doing.’

At the end of each diary entry John records the position of the ship. On Christmas Day they were at latitude 17.33 S, longitude 99.7 E and distance 319. This tells us that the RMS Oroya was somewhere in the Indian Ocean nearing the coast of Australia’s Western Territory.

On 31 December, New Year’s Eve, John writes about an outbreak of the measles, with nine new cases this day. He and all on board hoped that they would be put into quarantine so as not to infect the rest of the passengers. At half past midnight he joined with all the hands in singing Auld Lang Sine when they returned below to retire to their bunks.

On New Year’s Day he writes they were all simply happy to have reached the new year safely and were looking forward to the end of their journey. The ‘Scotch folk’ on board had a party that evening; ‘I was invited and spent a very pleasant evening. The best since I came on board…I may tell you that I am taken for a Scotsman by nearly all on board and as I have got back my Glasgowen tongue I can pass for one very well.’

On 2 January they anchored in Adelaide Bay but due to the measles they were not allowed on shore, apart from those who were bound for this port.

The last entry in this journal is dated 4 January 1889; ‘This has been an exceptional passage, there was neither birth, death nor marriage’. He counts himself lucky as he wasn’t seasick like many of the others and did not miss one meal since leaving London, something which he is very proud of! The ship docked in ports such as Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney and finished its journey in Williamstown, Victoria.