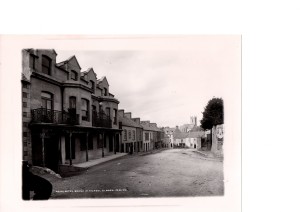

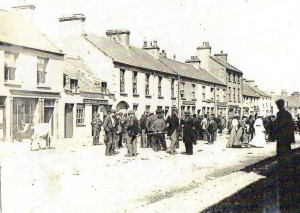

The vast majority of the people in Mourne would have lived in small rural cottages or houses situated along the main street in the town. Hanna’s Close is a good way to get feel for what life was like living in small rural cottages. This cluster of cottages were built in the 1600s by the Hanna’s who came to Ireland from Scotland around 1640. The dwellings were all built close together with only one door facing into the close and a few small windows at the back. This was to protect them from attacks. The Close is situated in the townland of Aughnahoory and in 1860 there were eight families of Hanna’s living in the Close.

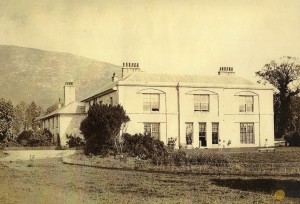

Those families who were better off would have lived in bigger houses of higher value and those who were very wealthy would have lived in ‘Gentleman’s Seats’.

Gentleman’s Seats in Mourne in 1823

Heartsfort : Thomas Pottinger

Jane-Brook : James Marmion

Kilmorey House : Viscount Kilmorey

Loyalty Farm : Lt. Col. G. Matthews

Mournepark : John Moore

Prospect : Alexander Chesney

Summer-Seat : Rev. Lucas Waring

Shannon-Grove : Francis Moore

White Water Mill : W. C. Emerson

Bellhill : John Waring

[Info. on Gentleman’s Seats from the Hugh Irvine Collection]